Adapting to Disruption

The pandemic has plunged the world into a new kind of uncertainty. So much has changed, and so fast. If someone had said last summer that by March 2020 thousands would perish daily from a new virus, 2.6 billion people would be locked down in their homes, 16 million people in the US would be out of work, and occupants of a California town would be howling at the moon together each evening, it would have seemed like crazy talk.

And yet here we are, living a new reality that no one yet fully understands. Some of us can even attest personally to the howling.

For those who work on nuclear weapons threats, the pandemic has an eerie tinge to it. As the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies’s Jeffrey Lewis recently said, the pandemic is a “nuclear war in slow motion.” Some of what we’re seeing right now resembles the kind of large-scale reworking of the world that will unfold if—or when—nuclear weapons are deployed again, whether by accident or by design.

We can’t yet know this pandemic’s full toll. But we can be sure that the consequences for the nuclear threats field will be significant. As we rebuild the economy, address inadequacies in emergency response systems, and anticipate the evolution of biological threats, nuclear weapons are unlikely to be top of mind for policymakers, funders, or the public. Yet in this crisis lies an opportunity to connect nuclear weapons both to an increasingly complex threat landscape and to our aspirations for global well-being.

By exploring intersections between nuclear weapons and other global phenomena—health and climate insecurity, the rise of artificial intelligence, racism and poverty, advancements in brain science—we can reframe nuclear threat reduction in terms of greater human and global security. We can draw resources and ideas to the field that would be elusive if we continued to silo nuclear weapons from other pressing challenges. The field’s ability to adapt to a more intersectional and complex environment, however, will depend on its capacity to embrace change and to innovate.

“IN THIS CRISIS LIES AN OPPORTUNITY TO CONNECT NUCLEAR WEAPONS TO AN INCREASINGLY COMPLEX THREAT LANDSCAPE AND TO OUR ASPIRATIONS FOR GLOBAL WELL-BEING.”

During our 2019 Listening Tour, many nuclear threat professionals we interviewed talked about the urgency of improving and innovating how the field itself works. They expressed a desire to embrace new tools and approaches—as well as concern that not doing so would make progress harder to achieve. The shock we’re living through now presents the field with a challenge: Will our organizations be sufficiently agile to survive? Will we “make due” so we can get through the crisis, or will the whole field be more resilient and resourceful afterward because of the adaptations we make now?

At N Square, we are reworking our own approach from top to bottom. Our mission remains the same: to accelerate the achievement of international goals for the reduction (and ultimate elimination) of nuclear weapons threats by attracting new human, technical, and financial resources; introducing innovation and design methods; creating collaborative environments and frameworks; and hosting an interdisciplinary, cross-sector network working to develop new solutions to concrete problems. But we also see an urgent opportunity to help nuclear threat professionals develop and hone critical skills for managing uncertainty and anticipating the future.

Here’s some of what you can expect from N Square going forward:

Remote Collaboration

For the next 12 months at a minimum, we are moving all our programming online. While we don’t take this decision lightly—convenings and face-to-face interaction are core to our work—we see so many potential offsetting benefits that we are committing ourselves wholeheartedly to the challenge. Fully remote collaboration will keep our extended community of fellows and partners connected and productive during whatever lies ahead and ensure that our projects move forward with full momentum. But we believe our experiment will prove useful to the field in other ways as well.

N Square already has an established track record of successful online collaboration. Our innovation fellows work largely in geographically distributed cohorts using distance collaboration tools; our staff also work remotely, giving us practice in how to run teams from a distance. But now we are taking that further. Already, we are analyzing and experimenting with new leading-edge platforms that use augmented reality and/or advanced interactivity to enhance remote collaboration and innovation processes. And we plan to share all that we are learning with the field, in service of fostering more flexibility and a new capacity to collaborate remotely.

You can expect to learn about these new tools through DC Hub brown bags, workshops, and virtual mixers in the coming months, as well as through new professional development opportunities using N Square’s learning exchange program on the distance learning platform TechChange. We will also share information about the compelling tools and platforms we’re discovering in our upcoming newsletters.

Foresight: Scenario Planning and Futures Thinking

The pandemic is a shock—but it’s not a surprise. For decades, scenario planners have been calling the outbreak of a global pandemic “predetermined”—not a “wildcard” event but one that was certain to happen at some point. Some of us at N Square have deep backgrounds at the intersection of scenario planning, strategy, and design. In fact our editorial director, Jenny Johnston, and I have worked for decades on futures projects in which bio-threats featured prominently. In 2010, as senior editor at Global Business Network, Jenny opened one of many scenarios on the topic with language that—while some details have played out differently—now seems generally prescient:

In 2012, the pandemic that the world had been anticipating for years finally hit. Unlike 2009’s H1N1, this new influenza strain—originating from wild geese—was extremely virulent and deadly. Even the most pandemic-prepared nations were quickly overwhelmed when the virus streaked around the world, infecting nearly 20 percent of the global population and killing 8 million in just seven months, the majority of them healthy young adults. The pandemic also had a deadly effect on economies: International mobility of both people and goods screeched to a halt, debilitating industries like tourism and breaking global supply chains. Even locally, normally bustling shops and office buildings sat empty for months, devoid of both employees and customers.

The pandemic blanketed the planet—though disproportionate numbers died in Africa, Southeast Asia, and Central America, where the virus spread like wildfire in the absence of official containment protocols. But even in developed countries, containment was a challenge. The United States’s initial policy of “strongly discouraging” citizens from flying proved deadly in its leniency, accelerating the spread of the virus not just within the US but across borders. However a few countries did fare better—China in particular. The Chinese government’s quick imposition and enforcement of mandatory quarantine for all citizens, as well as its instant and near-hermetic sealing off of all borders, saved millions of lives, stopping the spread of the virus far earlier than in other countries and enabling a swifter post-pandemic recovery.…

The value of scenarios doesn’t lie in the degree to which they prove true. Scenario planning is about preparedness. It’s about envisioning a range of plausible futures in order to inform strategy and “rehearse” responses to change before it happens. Scenario planning and other forms of futures thinking also help to override the human inclination to avoid exploring downside scenarios. They help us face and prepare for a range of circumstances.

“WHAT ARE WE NOT THINKING ABOUT TODAY THAT WILL AFFECT OUR CAPACITY TO RESPOND EFFECTIVELY TOMORROW?”

In the nuclear threats field, we need to be thinking about the ways in which social, technological, environmental, economic, and political forces will combine to change the context in which we do our work over the coming months and years. How will our challenges change—and how will we adapt—if bio-threats like this pandemic combine with natural and climate-related disasters like wildfires and earthquakes? How might the politics of nuclear threat reduction shift? In what ways must we be better prepared? What are we not thinking about today that will affect our capacity to respond effectively tomorrow?

In collaboration with colleagues from the professional futures and design worlds, N Square is fast-tracking plans to offer virtual trainings, interviews, and workshops on strategic foresight. We expect these to be available in the summer of 2020.

A few closing thoughts:

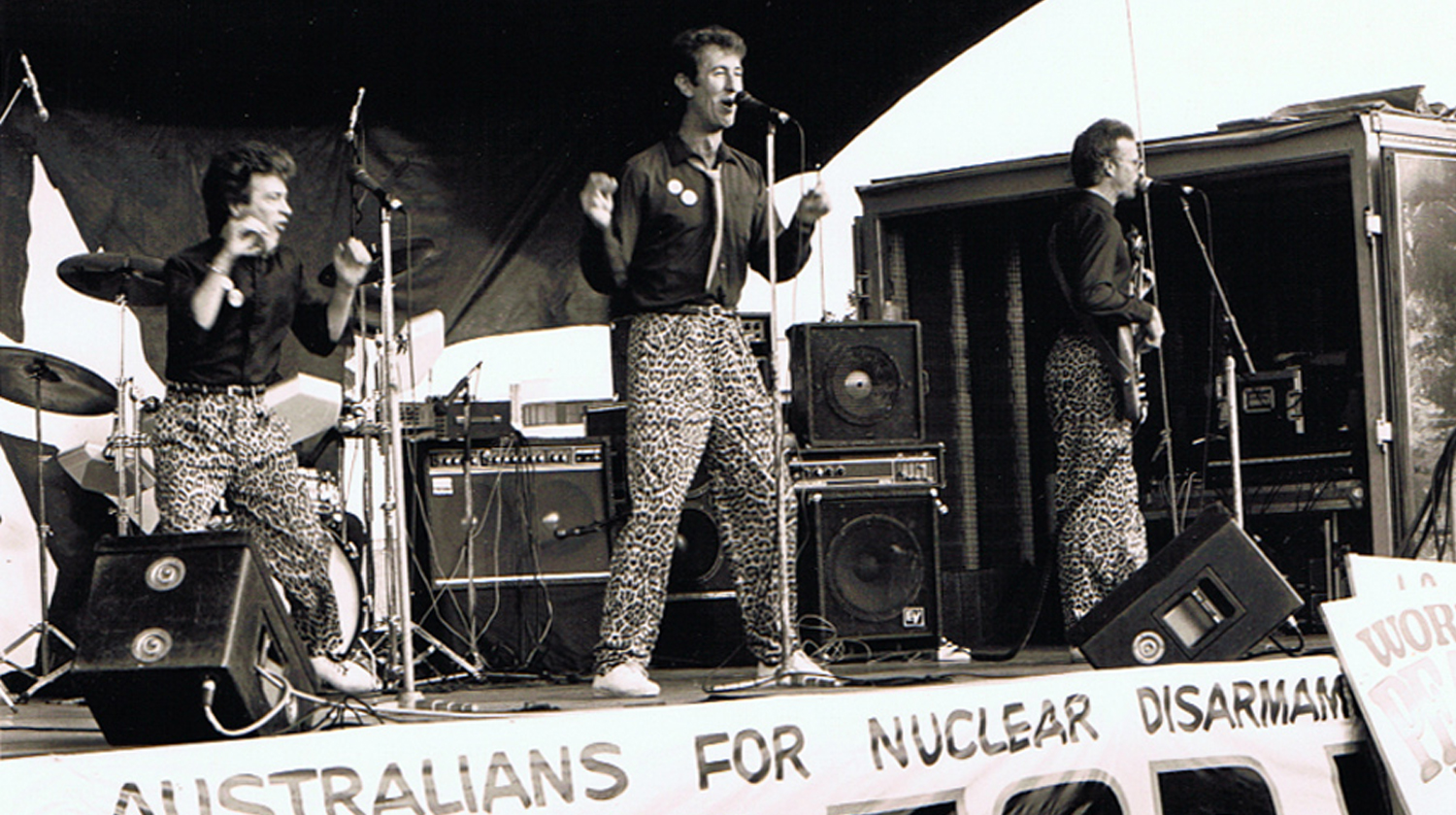

This photograph was taken on a street corner in my hometown in 1918, during the influenza pandemic. It seems that over a hundred years later we are using some of the very same solutions to protect ourselves from an invisible enemy. Will we be using the same solutions a hundred years from today? Isn’t it our job to make sure that in the next century we have new tools to cope with evolving threats?

We are a long way from knowing how life will play out right now. But we do know this: More shocks will come. Each will reveal systemic fragilities. The key is to strengthen our ability as a field to communicate and respond to the ways in which nuclear threats interrelate with those fragilities, and to become more resilient, resourceful, and influential as we do.

Story thumbnail photo: Patrick Criollo; top photo: Marius SSR, Shutterstock.com; bottom photo: Courtesy of the Lucretia Little History Room, Mill Valley Public Library