The Scholar

Emma Belcher grew up in Australia at a time when anti-nuclear movements in that country were flaring—an experience that shaped both her perspectives on nuclear weapons and her career. An early interest in nuclear policy led her to Tufts University’s Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, where she earned a PhD in international security with a focus on weapons of mass destruction. While there, she also served as a research fellow at the Belfer Center’s Project on Managing the Atom. Belcher’s academic career took a surprise turn, though, when she was presented with the opportunity to join the MacArthur Foundation, where she now directs the nuclear challenges program. Here, she shares how being an Aussie informs her work, and how she’s working to find common ground—even among unlikely partners—in service of ending the nuclear threat.

Q How did you get started doing this work?

A You know how people remember where they were when a big event happens, like JFK’s death or 9/11? I remember the room I was in when I learned about nuclear weapons. I was 14, sitting in social studies class. I remember being astonished by the damage they could do. To be honest, I was appalled and awed at the same time. The logic of deterrence and mutually assured destruction seemed kind of brilliant, even though it was horrific. This was toward the end of the Cold War, but growing up in Australia I hadn’t heard much about it. At 14, I was shocked by the state of the world.

At the end of high school, though, I got interested in Cold War history. At university I did an arts degree and studied politics, history, and languages—specifically, Russian and Arabic. I also became interested in the ethics of the use of force. Questions about nuclear weapons and whether they conformed to the laws of war started to grip me. My first job out of university was in public affairs at the Australian Embassy in Washington, DC. Then, just as I’d decided to go to grad school and get more involved in policy, 9/11 happened. That tragedy solidified my interest in weapons of mass destruction, and the possibility of nuclear terrorism brought new urgency to my work. Ultimately, I did a master’s in law and diplomacy at Tufts University, and after working as an adviser in Australia’s Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, returned to Tufts to complete a PhD in international relations, with a focus on weapons of mass destruction.

“QUESTIONS ABOUT NUCLEAR WEAPONS AND WHETHER THEY CONFORMED TO THE LAWS OF WAR STARTED TO GRIP ME.”

While at Tufts, I also had a research fellowship at the Belfer Center at Harvard, at the Project on Managing the Atom, which is still funded by MacArthur. I was part of a cohort of PhD students from a range of institutions working on similar topics. We learned from one another in ways that we couldn’t at our own institutions, where there weren’t a lot of other people working on the same topic. I remember I could always go to my friend Tom, who is a physicist, and ask him if my ideas made sense from a physics perspective, and I could help him see his work through an international security lens. That experience taught me the importance of being in community with people who are working on similar issues but from different perspectives. Of course, that’s the premise behind N Square as well.

Q How did you get into philanthropy?

A When I finished my PhD, I did a post-doctoral fellowship in nuclear security at the Council on Foreign Relations. While there, I got a call from the head of the Managing the Atom project. He said that MacArthur was looking for a nuclear program officer. I had never thought about a position in philanthropy, which isn’t established in Australia in the same way that it is in the US. At first I thought it sounded kind of boring. How hard could it be to give away money? How was a PhD going to help with this? But the more I talked with people, the more I realized how interesting it was. The research skills I had developed were helpful in analyzing the quality of proposals. I realized philanthropy could combine my academic interest in nuclear policy with a more practical policy focus.

“HOW HARD COULD IT BE TO GIVE AWAY MONEY? HOW WAS A PHD GOING TO HELP WITH THIS?”

Q Do you think you have a different perspective on nuclear security because you didn’t grow up in the United States?

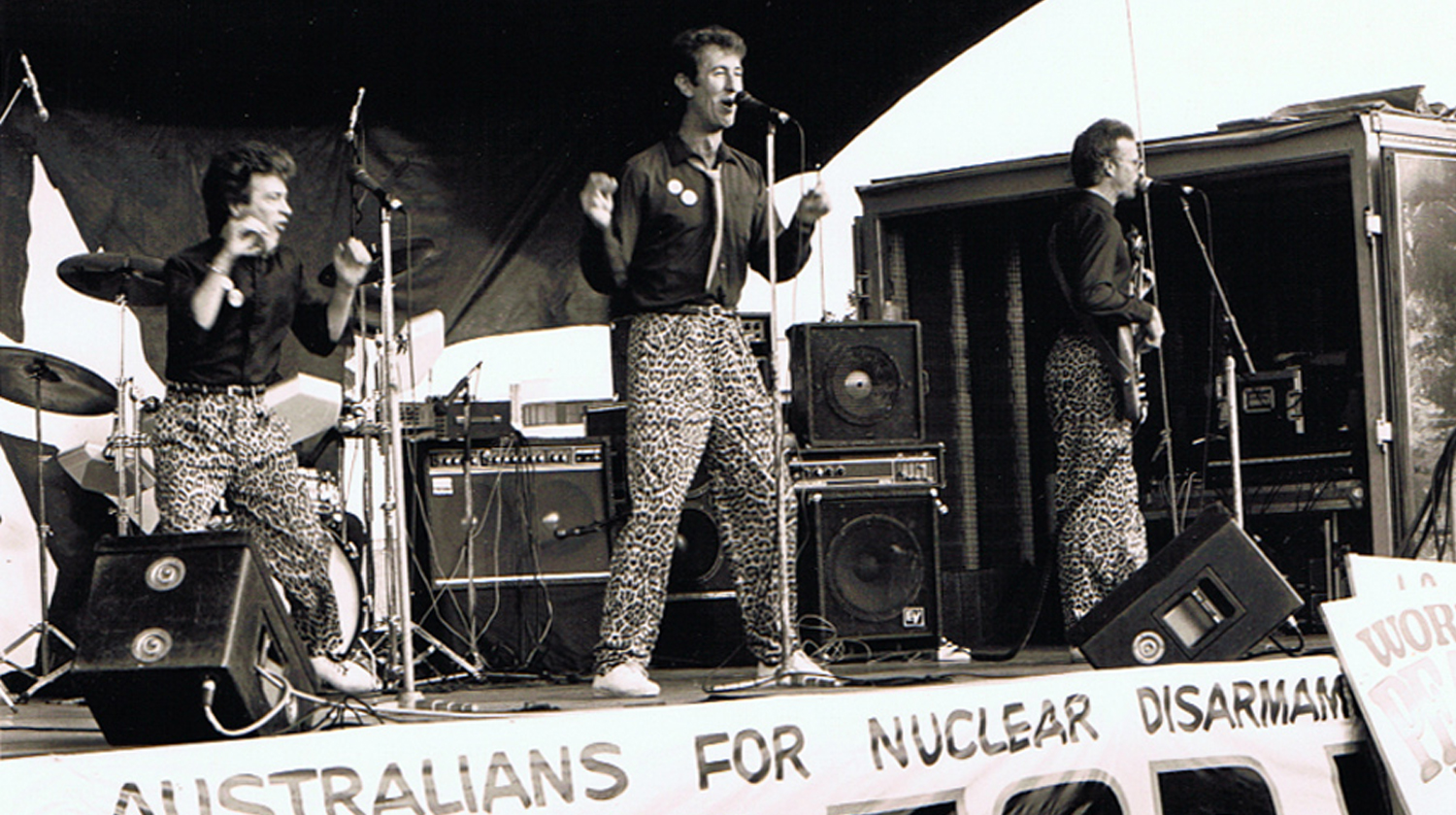

A I think it gives me a sense of how nuclear weapons in the United States are viewed by outsiders, which is something that can get a bit lost here. Growing up in Australia, there was a strong nuclear disarmament movement, particularly in the ’70s and ’80s. I was in high school when the French were doing their testing in Mururoa Atoll, and we were up in arms. Seeing the impacts of nuclear testing and fallout on people and on the environment was quite formative. At the same time, I also understand the issues and the concept of deterrence and how difficult it can be to imagine a world without nuclear weapons. In the US, many people on both sides of the issue are deeply entrenched in their positions; they’re not willing to talk with each other in a meaningful way. As a funder it is crucial to see both perspectives and support constructive dialogue.

Q MacArthur is one of the few foundations with a specific grantmaking program to reduce the nuclear threat. Why aren’t more foundations funding this issue?

A When the Cold War ended, many people assumed that the threat was over. The US and Russia dismantled a great number of weapons. At the height of the Cold War there were between 60,000 and 70,000 nuclear weapons, and it’s down to around 14,000 today. People thought these weapons would become a relic of the past, and with a number of other important issues rising to the surface their attention was diverted away. But now these issues are back with a vengeance—and we need to rally more people to invest in finding solutions. Foundations are collectively investing around $40 million in nuclear policy, versus nearly $1 billion a year in climate issues. So we’re hoping to bring more funders back into the field and new ones to it—and to help everyone recognize this as a dangerous, existential threat. A nuclear event could happen very quickly with very little warning.

Q What has MacArthur been funding in this area?

A Our grantmaking has been focusing on trying to make sure that members of Congress and their staff have a good understanding of contemporary nuclear issues. Just as we’ve seen funding levels drop since the end of the Cold War, we’ve seen a similar drop in general awareness about the nuclear threat in Congress. Champions like Sam Nunn and Richard Lugar have retired or are no longer with us. We are starting to see new champions emerge, which is promising. There’s now a bipartisan nuclear security working group on the Hill, co-chaired by Republicans Jeff Fortenberry and Chuck Fleischmann, and Democrats Bill Foster and Ben Ray Luján. We provide funding for fellows to serve as advisors on nuclear topics. They don’t work on legislation, but they’re embedded in both chambers as a resource for members. We also support experts who provide technical and practical advice to government officials here and in other countries on how best to solve a range of nuclear problems.

Q How has being part of a nuclear security funder collaborative—which is funding N Square—advanced your work?

A Each funder in the collaborative brings something different to the table. Our differences complement each other and help us explore the potential for overlap. Being part of a funder collaborative is also about sharing risk. Being “in it together” means we can make venture-style investments without having a failure devastate any one of our portfolios. It also sends a signal that a group of us are interested in funding more innovation and creativity in the field. We hope it helps many more individuals and foundations see themselves as having something to contribute here. Nuclear weapons can seem like this big secret national security topic, which makes the issue uninviting for some. If we could start to change some minds and have people see where they do fit in, even if they don’t have a nuclear background, that’s valuable.

Q In a recent TED talk, you outlined a set of questions that everyone should be asking right now about nuclear security and nuclear weapons. What sorts of questions were on your list?

A I put that list together as a way to help people begin to work past fear or a sense of being overwhelmed and instead start doing something to ensure that this issue gets the attention it deserves—questions like, How much nuclear risk are you willing to take? Or, Who should be responsible for nuclear weapons decision-making? For example, in the US, having one person, the president, decide the fate of millions of people without any requirement to consult with anybody seems particularly undemocratic. Also, What do your elected officials know about nuclear weapons, and what decisions are they likely to make on your behalf? Members of Congress represent their constituents, but right now there isn’t a constituency for nuclear issues. We need to create it. We need our elected officials to understand these issues, because they’re voting and making decisions about our future.

“RIGHT NOW THERE ISN’T A CONSTITUENCY FOR NUCLEAR ISSUES. WE NEED TO CREATE IT.”

Q Can nuclear security be depoliticized? Is there room for compromise?

A Everyone can agree that we need total security around weapons and nuclear material, and nobody wants to see nuclear terrorism. So that’s a starting point. Over the next several decades, about $1 trillion is projected to be spent on nuclear weapons, which is a lot of money. Even where you don’t get bipartisan support on some of these bigger issues, we might see unusual partners coming together around shared goals, even if they’re coming at them from different perspectives. That is, while disarmament is seen as a liberal imperative, fiscal conservatives are less likely to support a massive modernization effort, given the associated cost. Where there is room for bipartisanship, we’ve got to push for it.

Q What do you think the nuclear field will look like in 10 years?

A I think it will look significantly different. We’re seeing increased diversity at the early career and even mid-career stages—and we’re actively working to foster more of it. N Square is providing young, diverse, talented people with new opportunities to engage in the field. If we take that out 10 years, we’re going to see much more diverse representation in the field. That’s critical because these issues affect everyone; everybody needs a voice. So I’m optimistic because I’m seeing this change happening and I’m seeing people demand it. I’m also seeing people who’ve been in the field for a while support these changes. They’re lending their gravitas and experience to this in a way I might not have expected. That’s been a fantastic development.

Q What would the future look like if everything goes well?

A We would see greatly reduced nuclear risk, greater creativity, innovation, and excitement around this issue, and a sense that people can create positive change. I’d like to see us pulled back from the brink of disaster. But we’re only going to get there through approaches to problem-solving that are creative, inclusive, and innovative.

Top photo, from left to right: Michelle Dover, Emma Belcher, and Eric Schlosser speak at Ploughshares Fund Chain Reaction 2019. Story thumbnail and top photo: Drew Altizer Photography