An Operating System for the 22nd Century

In early April 2023, N Square held its sixth annual Innovation Summit, featuring the work of the latest cohort of N Square innovation fellows, a diverse mix of academics, activists, military instructors, and experts in finance and media. While past cohorts have presented multiple projects and prototypes at their summit, this cohort organized its work around one big speculative question: What might a world in 2095 without nuclear weapons look like? What would need to be true? What would we need to overcome, invent, or do differently to get to a new framework for global security? Over the course of several months, the fellows pushed the boundaries of what’s imaginable today in order to punch through to a vision of a far different future. The end product of their speculative work was a kind of guidebook exploring and detailing a new operating system for the 22nd century.

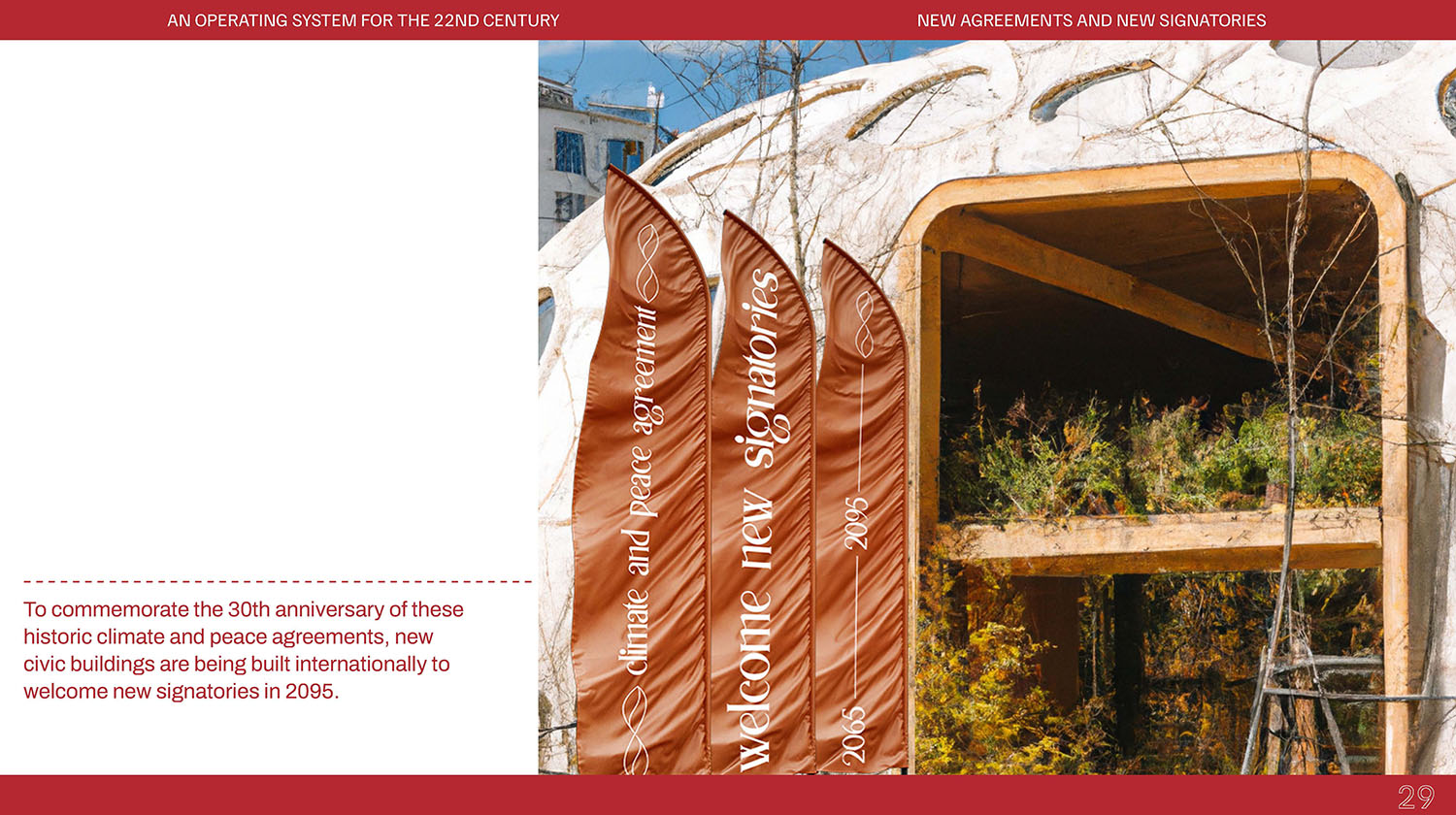

At the Innovation Summit, which was held online, the fellows described the operating system as a framework of structures and systems that organize global efforts to maintain planetary and human security, focused on four main elements: a new security architecture, new policies and forms of citizenship, new ledgers and accountability, and new agreements and signatories.

The summit featured three panel discussions. In the first panel, fellows introduced the OS and discussed the first element: a new security architecture. Fellow Aditi Verma, an assistant professor in nuclear engineering and radiological sciences at the University of Michigan, explained that in order to achieve a world free of nuclear weapons, security needs to be redefined as the intersection of human and environmental security. She also said that equitable and participatory design of the requisite technology for that redefined security is essential.

Julia Gorbach—filmmaker, creative director, strategist, and founder of Wild Minds—talked about decentralization and the intersection of nonhuman species communities, digital communities, and cultural communities. What if, for example, the digital group Afropolitan became sovereign? Learning how to communicate and sustainably coexist within a spectrum of community types will be a feature of the future these fellows envision.

“We’ve been looking at the world through a human-centric lens and there are so many different species that coexist with us,” Gorbach said. “So if today, in 2023, people are able to know when a plant is thirsty and when they should water it, think about what [the future] looks like when we also have nonhuman species who have sovereign power.”

Lyndon Burford, N Square’s network weaver and cofounder of Path Collective, added that a decentralized future requires greater transparency. Humans depend on ecosystems for food, clean water, and air so it’s important to understand how those ecosystems are being impacted. Burford suggested viewing coexistence in a similar way to how we think about sharing air and rivers.

“River systems flow from one nation’s territory into another. The air passes from a nation’s airspace into another and they recognize that inherent interconnectedness,” Burford said. “If we move to a system where we have a greater awareness of these types of flows of water or air, we’ll have to also move it into a political system whereby we recognize that in our agreements and make space for that with each other.”

In the second panel, the fellows discussed other ways the world needs to change for this new operating system to be possible. Lieutenant Colonel Brian Novoselich, chief of staff at West Point and an innovation fellow in this cohort, said those changes include enabling societies to secure themselves not just militarily but also fundamentally in terms of meeting basic human needs. He highlighted some of the ways that current threats impede the path to a more secure future.

“If you look at disrupting national elections, persistent cyber threats to national infrastructure, and the degradation of trust in the idea of truth, not only do we have substantive challenges on the horizon for human welfare, but now we have challenges to the very societal structures that have been put in place for nations to mitigate those threats,” Novoselich said.

Burford suggested that mindsets will shift gradually as people see the increasing intersection of challenges. He gave an example of inkblots coming together on a sheet of paper. “As the inkblots spread, they start to intersect. Any one of these [challenges] might not be enough to shift thinking in dramatic ways, but as they start to intersect, populations of real human beings start seeing these things coming at them from different directions and realizing that the systems that we’re trying to think in today are not working, because there are all of these new challenges arising.”

The changes that need to happen can be overwhelming to think about, noted Katherine Collins, head of sustainable investing at Putnam Investments and another member of the fellowship cohort. She emphasized the importance of having hope and being able to switch from the head to the heart when dealing with these concepts.

“I think of hope as something that’s increasingly important in a lot of our settings. Hope not like sunshine, puppy dogs, and teddy bears hope, but a tough kind of hardened hope,” Collins said. “If you’re thinking of Pandora’s box after all the evils of the world play out, it’s what is left at the bottom—it’s this battered-up tiny creature with wings.”

“I THINK OF HOPE AS SOMETHING THAT’S INCREASINGLY IMPORTANT IN A LOT OF OUR SETTINGS. HOPE NOT LIKE SUNSHINE, PUPPY DOGS, AND TEDDY BEARS HOPE, BUT A TOUGH KIND OF HARDENED HOPE.”

Finally, in the third panel, the fellows talked about using the operating system as a tool for provoking different ways to think about security, a lens for observing and making sense of emerging conditions, and a guide to contextualizing current efforts.

The fellows designed the operating system to be accessible to diverse audiences, hoping to draw more people into sharing and contributing to it without having to be security experts. “Invit[ing] people from all different parts of the world, all different industries to come and play together” might be a challenge, Gorbach said, but everyone should have a hand in designing a more secure future. “When it comes to security, we’re all impacted.”

The fellows included Leo Blanken, Jeanne Bourgault, Jess Brown, Lyndon Burford, Katherine Collins, Julia Gorbach, Brian Novoselich, Kiki Nyagah, and Aditi Verma.

MORE:

- Explore the fellows’ operating system for the 22nd century.

-

Watch the Innovation Summit recording (below).